By: Marshall Bursis

American car-dependency is a pernicious form of unfreedom. Our movies, music, and mythology mistakenly equate opportunity and the car. In 1928, partisans for Herbert Hoover famously promised voters a chicken in every pot “and a car in every back yard.” Yet, cars are not the liberty-machines many think them to be. In practice, our reliance on personal car ownership makes us less mobile, our economy less dynamic, and all of us less free.

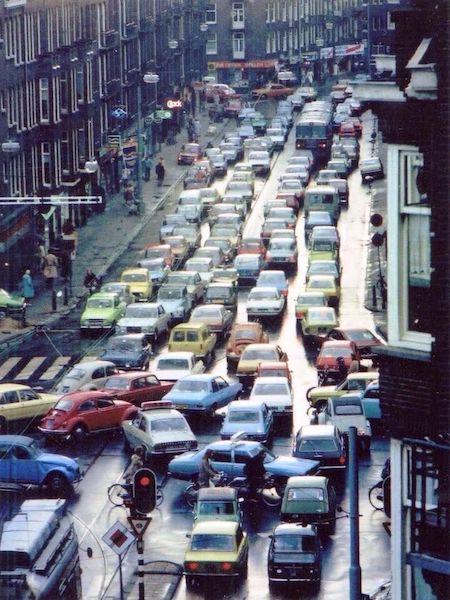

The myth of the open road distorts American life. Road trips consume our vacations. Commercials promise adventure—featuring cars anywhere but an actual road. For many, attaining a driver’s license is the mark of adolescent independence. Yet, instead of the unencumbered freedom many expect, the daily experience of driving in America features increasingly long commutes and routine congestion.

The reality of our automotively saturated society defies expectations. Today, American households have near universal access to a private vehicle. But, despite this widespread availability, fewer are choosing to live further from home. According to the Census Bureau, 60% of today’s young adults (those born between 1984 and 1992) live within 10 miles of where they grew up. Only 20% of this cohort lives more than a 2 and a half hours’ drive from home (100 miles or more).

This is highly unusual in American history. Migration rates are lower today than at any period since the Census Bureau began tracking the statistic in 1947. Mobility rates are at historic lows both within and between counties. Fewer than 10% of Americans are changing residences at all. Only 3% are moving to a new county—fewer still to a new city or state.

What accounts for our lack of mobility? One answer, from economist Tyler Cowen, is that high housing costs—driven by exclusionary zoning—have made moving more costly, forcing the poorest Americans away from the richest metro centers and towards cheap suburbs in the southwest and southeast. As summarized by writer Derek Thompson in The Atlantic, “moving toward affordability has replaced moving to opportunity.”

But there’s another, even more obvious explanation: cars are causing us to stay put. He and other writers miss the separate and somewhat related impact our culture of car-dependency has on declining mobility.

First, there’s the high financial cost of owning a car. A 2022 report from the American Automobile Association (AAA) estimated the average yearly cost of car ownership at close to $11,000. The freedom to live without a car would afford many would-be movers an almost $900 monthly rent payment. In cities where some residents are able to escape the daily costs of car ownership, they nevertheless spend a hundred dollars or more each month on rideshare apps.

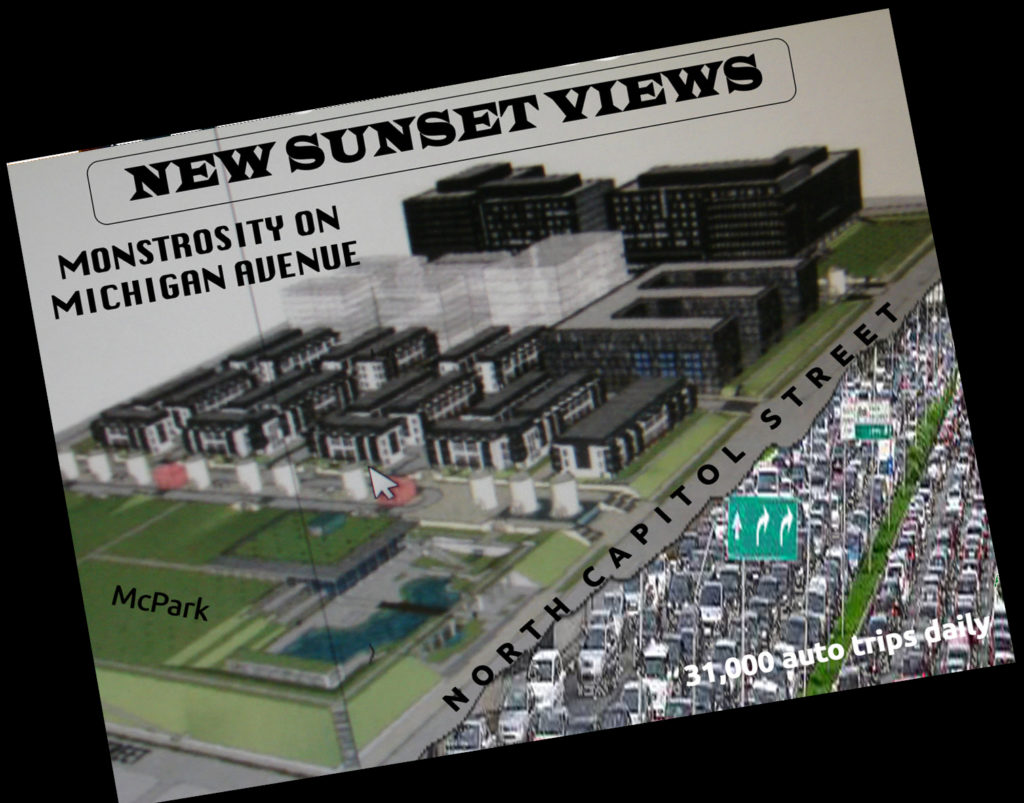

Additionally, many of those land-use policies Cowen faults are themselves connected to car-ownership. Throughout major cities, mandatory parking minimums often require developers to set aside more land for parking than actual construction. This regulation reduces land available for housing and increases construction costs for developers, who pass those costs on to tenants in the form of higher rent—whether or not they have a car. The Charlotte city council only just approved in 2021 its first parking-less building over the objection of locals concerned about the availability of on-street parking. In Washington, DC, even when city planners and developers satisfy parking fears, some object that an increased housing supply will mean more drivers and more traffic.

The consequences of our geographic immobility affect not only those stuck at home but also our economy and culture. Cowen warns this new stasis is a threat to the dynamism that fuels the American economy. He cites research concluding that if Americans could more freely move to high-productivity centers, GDP would be 9.5% higher and unemployment much lower. More metaphysically, he argues that staying put threatens the unique American capacity for innovation, dynamism, and renewal. The decision to stay at home has, he writes, “sapped us of the pioneer spirit that made America the world’s most productive and innovative economy.”

Our cities should promote forms of transportation and housing that free residents–and would-be residents–from the costs and constraints of car ownership. Bikes are virtually free, create almost no traffic, and require far less space for parking. Buses and subway systems are inexpensive for users and cost-effective for cities. Cargo electric bikes can replace cars.

Policymakers, planners, and consumers should reconsider America’s century-long relationship with the car. And, when it comes time to move, Americans should leave the car at home and rent a U-Haul instead.